| Home page | Subscribe (print edition) | Selected articles | Our publications | Our mailing lists |

| PDF edition | Subscribe (PDF edition) | Back issue contents | Autism books | Contact us |

From Volume 2 Number 10

Search for books by Professor Gary Mesibov

One of the world's leading autism experts, Professor GARY MESIBOV, director of Division TEACCH in North Carolina, in the United States, spoke to ADAM FEINSTEIN, Editor of Looking Up, about his programme's approach to educating children with autism

ADAM FEINSTEIN: I'd like to start with an intriguing recent observation you made during a talk in the United States. Everyone agrees on the importance of intervening early in educating autistic children. But you pointed out that there was a second early intervention window opening up at puberty. I was fascinated by that. Could you do go into a little more detail about this?

GARY MESIBOV: I was also fascinated by this. It is not my work – it was written up by an autism researcher, Catherine Johnson, It was interesting from the perspective of how we think about autism. It was also interesting because we do see certain children with autism who seem to have growth spurts around puberty. We see them developing, improving their capability., You see some children start to talk, when did not have much communicative language earlier. When I was at graduate school, we learnt that, if a child does not talk by the age of five, he won't talk at all. Although they modified this, the line was still that, if the child did not talk by 10 or 11, then forget it. But now we see language appearing at puberty. We see hormones at that age, in autism as well, which sometimes interferes with development., But if it doesn't interfere, we see development. Where I see the biggest growth spurt at that age is in social interaction, social relationships. You do have the issues of adolescence, hormonal and biological. In autism, we sometimes have the additional problem of developing seizures at that age, which is pretty unique to autism.

AF: TEACCH aims to be flexible, and it tries to move to adapt its strategies to the latest research findings. How do you see TEACCH applying the latest findings about the second intervention window?

GM: I don't think we ever thought about it from a neurological perspective, but one thing has changed in the way we work with people with autism. We have always had this basic structured teaching strategy philosophy – trying to teach them to use and capitalise on their skills. I can't really say it's because of the neurological findings, but one of the things that we started to notice in our adult programmes is that there almost needed to be a second level of structured teaching. Children not only needed to learn to use schedules but to be more flexible within those schedules. We found that, sometimes, the children were just memorising the schedules. So if there were no chicken fingers for lunch on Friday, for example, a child would have a tantrum. That really should not happen if our system is being used right, because the child should not memorise the schedule but rather be able to look at it each day and change it. They should have a more flexible way of dealing with the world, using the schedule. We are really focusing now on schedules and systems featuring more meaningful skills. The neurological findings suggest that these children should be capable of this, because they are making cognitive advances and expanding.

AF: You are partly talking about generalising skills here. Critics of the Lovaas-Applied Behavioural Analysis approach suggest that it does not encourage this generalisation, don't they?

GM: Yes. In fact, our system developed based partly on those criticisms. It is particularly important to us to give as much support as possible towards generalisation.

AF: Would it be too simplistic to say that the fundamental difference between TEAACH and ABA-Lovaas is that ABA is based on the principle that the child must overcome his autistic characteristics and adapt to the world around him, while TEACCH provides the child with an environment designed to accommodate the characteristics of an autistic child?

GM: Well, of course, the situation is more complex. There are two ways of looking at it. I think there are two important differences between the two approaches One is philosophical: ABA, Lovaas or discrete trial training works on the basis that, with some form of intensive, systematic teaching, you can acquire a "normal" or neurotypical model, I think the word "accommodating" for what TEACCH does might give the false impression that we don't teach children with autism. Of course we do. Now, I myself am terrible spatially and I have the worst memory ever – and it's getting worse as I get older! But these are things that children with autism are good at, so we try and enhance their strengths and develop around some of their interests, to try and help them function more comfortably. It's not a question of accommodating. The difference is what we teach. ABA-Lovaas is teaching the more "normal" model of development and functioning, while we at TEACCH are trying to expand around the differences. Both are looking for development and progress, but the emphases are slightly different. The other big difference between us – and it's not talked about as frequently as the philosophical difference – is that the major concept behind ABA and discrete trial training is that reinforcement is the main trigger for development and learning. They believe that, if something positive follows a behaviour which is very systematically and precisely taught, then that behaviour is going to increase. Whereas I think that the TEAACH comes more out of the Gestalt tradition, which focuses on meaningfulness and understanding. My argument is that, if a thing makes sense to someone, if they understand it, then it is going to promote their learning more effectively. It's a real challenge for anyone – especially someone with autism. If you put me up against Dr Lovaas or any ABA person and said: "You have one chance to work with this child and whoever works most effectively wins the battle, " what they would try and in is the most powerful reinforcement, whereas I would try and get a concept to make sense to the child, to communicate understanding. This difference of technique is important.

AF: Do you find that some of the people who have shifted away from the original UCLA approach to Lovaas are moving closer to your approach? I am thinking specifically of Lynn and Robert Koegel, with their emphasis on motivation and pivotal response.

GM: Absolutely., I look at their pivotal response concept and I would probably interpret it in a different way – but I agree entirely that the notion of motivation brings in much more the person's understanding and the personal connection to what you are teaching. Whereas in the ABA-Lovaas, discrete trial training approach, everyone learns the same thing. Lynn Koegel just did a study that I would have been very proud to have done in which she was trying to develop social interests and skills, around the interests of the children. This is a very strong TEACCH concept. Some of the ABA extensions – and the Koegels are a good example – are closer to what we do than to discrete trial training. They are also doing them in natural environments. ABA is a funny term. One day, I would like to figure out whether structured teaching or TEACCH is ABA! Some of the people doing ABA are working with priorities which are closer to what we are doing. They do it in a natural setting. They do not focus on language but on communication. Lynn Koegel was recently at one of our conferences, and she talked about initiating communication, which is the kind of problem which we worry much more about, because it is such a problem in autism. But I still think that the distinction is between reinforcement and meaningfulness. And yet – and I'll let you into a secret here! – you can come into our programme and you'll see people using reinforcements. After all, reinforcement works. We get paid to work, and if we don't get paid, we don't work as well. The world operates on that principle. We don't deny that principle, And the ABA people are focusing more on interests and things that there are meaningful. But there is still a legitimate distinction between TEACCH and ABA-Lovaas. We would look first at meaningfulness, whereas they would look first at reinforcement.

AF: What do you think of the National Institute of Mental Health's recent decision in the United States to stop funding the Koegels' research, on the basis that it is educational and not medical research?

GM: That's bad. Of course, they're right to say that the studies are educational. And when the NIMH and the National Institutes of Health talk about treatment, they are talking more about biomedical treatment - which I think is unfortunate. The record of educational treatments in terms of advancing people with autism has done a lot more than diets or drugs or medication. I would like to see the NIH sponsor more educational treatments.

AF: That does bring us to the question of scientific research on educational programmes, which is a continuing source of dispute. Where do you stand today on Lovaas's continuing contention that his 1987 study and the 1993 follow-up remain the only stringent studies to date in this area?

GM: I don't think that is true. In fact, I'm almost reluctant to discuss such issues, because I think that talk about "curing" children with autism or scientific strategy are distractions. I think it is extremely difficult to evaluate any intervention in autism. Of course, we can look at Lovaas's study and criticise it, because that is the nature of what we do. We can criticise anyone's study, because that would motivate us to produce better studies. But to claim that his is the only scientific study – well, if it is, we would all be out of job, because that 1987 study used aversives, slapping children on the knees. We no longer slap children on the knees. So if we are going to use that strict criterion, we would all be out of business – because no one uses that strict form of ABA any more. Obviously, we think there is more to it than that, and we hope we will get better and better evaluation techniques.

AF: Turning specifically to TEACCH, in the late-1970s, there was a shift away from training parents to training professions. Is there an imbalance today? Or are the two vital elements in the TEACCH "mix"?

GM: We still do both. Actually, we have recently had an increase in the numbers of parents being trained. It really came with the start of school programmes: the reality that, when we began the programme, there were no school programmes and children were spending all day with their parents. The kids still come to our clinics, we still do the diagnostic work.

AF: And you are now expanding to many other countries. Is there a prior level of understanding of autism required in a country for a TEACCH programme to be implemented?

GM: It really depends on the people involved. One of the most inspiring and effective people I know is a paediatrician and mother of a child with autism living in Nigeria. She is working in circumstances as difficult as anywhere in the world. She has visited us in North Carolina many times, and she is extremely knowledgeable. I haven't seen her programme myself yet , but the videos I've seen are impressive and she has had a tremendous impact. The power of TEACCH is that there is no one strategy or technique. The basic concept of trying to use the strengths of children with autism and help the child to make sense of the word can take you in a lot of different directions. I think a more developed country is more likely to use the TEACCH programme in a more similar way to the way we use it in North Carolina. But I would say that TEACCH is the most widespread programme because it is designed to be used by many different cultures, which can develop it in their own way.

AF: The British education authorities continue to lay great emphasis on the importance of mainstreaming special-needs children – including, of course, children with autism. Where do you stand on the question of inclusion?

GM: Where you focus more on philosophy than on the children, you are doing a disservice to the children. I don't think you can ever make a categorical statement like that about autism.. If the children with autism who can benefit from mainstreaming can get it, that is good. But there are always going to be children with autism who are not best served in a mainstream environment. There are a lot of arguments to support this. The simplest is that these children will not do well in a mainstream environment because "normal" kids are noisy, they run all over the place. There are all kinds of sensory stimuli which will disrupt children with autism. If you had put Temple Grandin, our most celebrated person with autism, in a mainstream public (state-run) school from the very beginning, she would probably never have made it through high school. Her parents had the wisdom – and the money – to put her into a small private school. Now she has a PhD.

AF: Can I ask you about regressive autism? My son, Johnny, was one of those who seemed to be progressing normally and then lost his language and other skills at around two and a half. I have spoken a lot about this to Lorna Wing [one of the world's great autism authorities] and she is adamant that there is basically no such thing as regressive autism. In other words, she insists that, when parents look back and appear to remember their child talking normally, that child, says Dr Wing, was never using language in a socially meaningful context, and so was already autistic. I have also spoken to US autism experts like Geraldine Dawson, Ed Cook and Joseph Piven and they have all revised their estimate of the proportion of regressive autism cases down from 25 per cent to about 10 per cent. But there are a number of people in the UK who see late-onset or regressive autism as a separate sub-type of autism, brought on, say, by "autistic enterocolitis" (a condition which the British gastroenterologist, Dr Andrew Wakefield, claims may follow the combined MMR vaccine in some cases ) or some other viral or toxic post-natal insult. What is your view ?

GM: We need more information. There is a real phenomenon of apparent neurological regression in children who follow normal progression up until 15 or 18 months., but I do not know that this has to be because of injections, the MMR vaccine, or because of a disease or insult. It could just be the normal course of autism. We have genetic conditions - like Alzheimer's – which people are not born with, Alzheimer's does not manifest itself until seventy or seventy-five, when people go into a very pronounced regression. No one looks at their history to see whether they received a vaccine. So we do acknowledge that there a lot of genetic conditions which occur at different points – they are just not associated with development. I do not think that, in order to make these conditions real, we have to find an environmental or immunological cause for them. The kind of regressive form of autism we know best is Rett's syndrome – although whether it should be classified with autism I am not sure. My understanding – from Fred Volkmar, who organised the DSM-IV field trials - was that regressive autism has about the same incidence as Rett's syndrome. Now, I've seen a couple of cases of this sort of regressive autism. There are not many things I do not agree with Lorna Wing on! But I do not agree with her on this. Because I have seen cases of autistic regression. I don't question its existence. But I don't think it's very common. When you look at sub-categories, there are other possible ones.

AF: Which?

GM: I wish I knew what to call them. Something possibly resembling Asperger's syndrome. We are always saying in our clinic: "Doesn't he remind you of those four kids we saw 15 years ago?" We see certain patterns in their cognitive skills and development which occur more frequently. This is one of the challenges in the field: to identify useful sub-types. Also, if you think about it, you see regression at different points in autism. There does seem to be come kind of neurological regression. I don't know of any other disorder where a third of people with the condition develop seizures during adolescence. We actually see some children - and I do remember Lorna herself talking about this when she visited our programme - who show some form of neurological regression in their early twenties. And we see some people in their thirties and forties who seem to be losing their skills. However, you never find this showing up on MRI scans or the neurological tests. But there are a number of examples in autism when neurological functioning appears to be lost when you would not expect it.

AF: Does it matter to you, as an educationalist, to know whether a child was born with autism or whether it was "brought on" later by some post-natal trigger?

GM: Well, we haven't figured it put yet! One of the most interesting things, I find, is that, when you look at the children with autism who develop skills and then lose them between 15 and 18 months, no one can later find any difference between them and the children who never developed skills. You would think that, as a clinician, you would be able to find a distinction. But you can't. That's surprising.

AF: You were saying that you found children who reminded you of others, but without a name. Does this imply that the DSM-IV and ICD-10 classifications of autism are defective?

GM: No. It means that we would all like more sub-types. We notice patterns, but then trying to identify and classify those patterns is hard.

AF: How about the general debate over rates of autism? Are they rising? Lorna Wing believes that the actual numbers of cases of autism are not going up but that the figures reflect improvements in diagnosis and broadening of the spectrum.

GM: I think Lorna is right, but I also think that, above and beyond those factors, there is also an increase. We have applied to get an epidemiology grant in North Carolina so that we can study this whole issue systematically.

Search for books by Professor Gary Mesibov

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Current 40-page print edition issue | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||

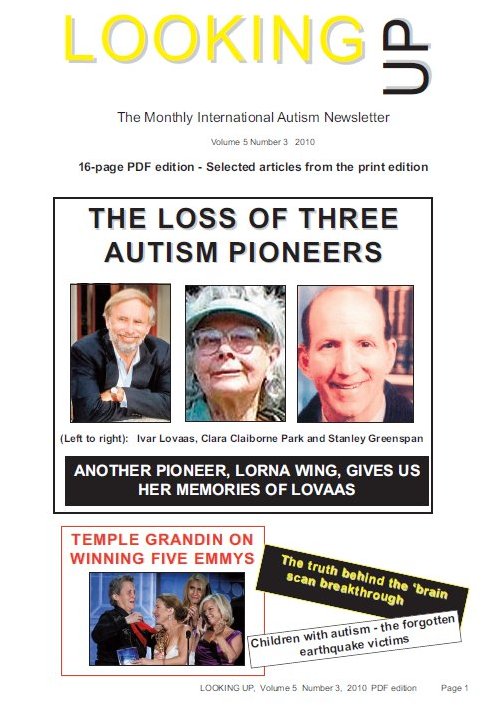

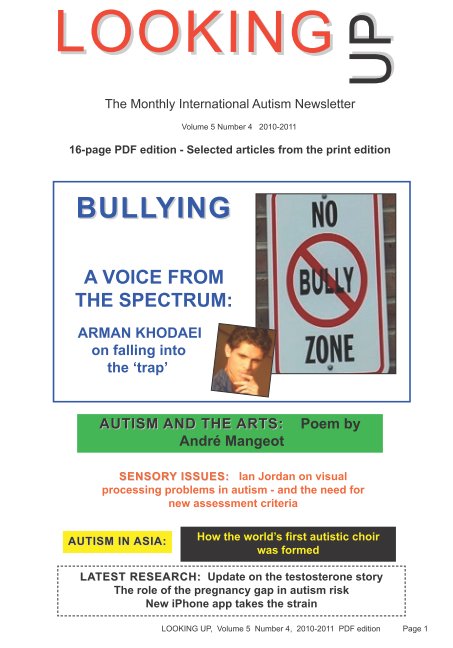

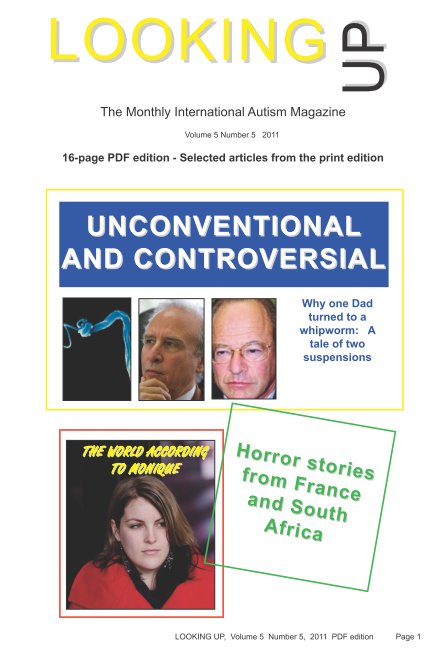

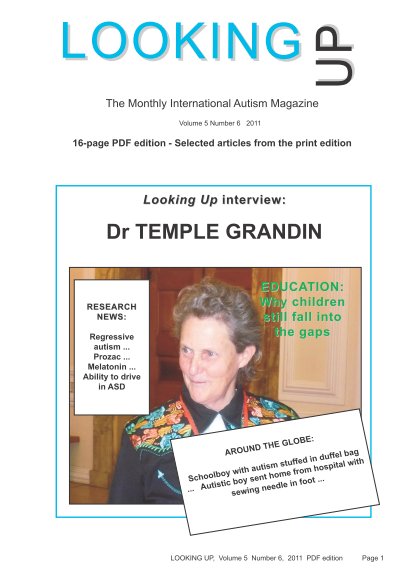

| PRINT EDITION BACK ISSUE CONTENTS AND FRONT COVERS | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

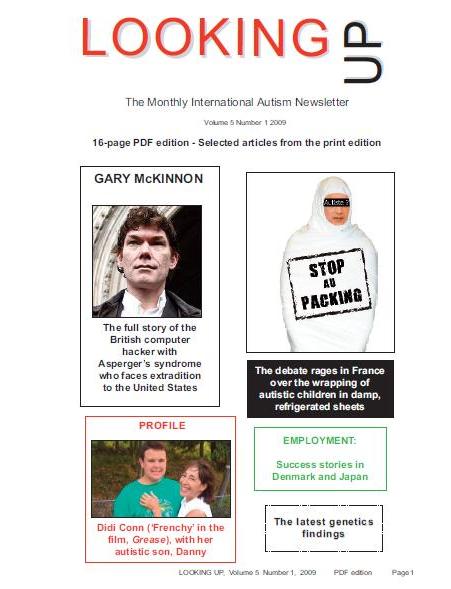

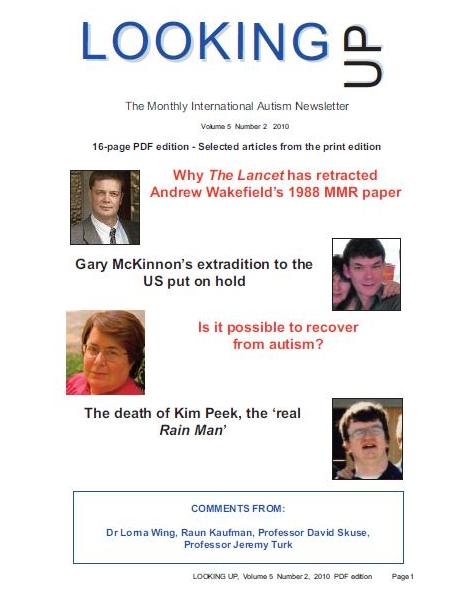

| VOLUME 1, Number: | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | VOLUME 2, Number: | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

| VOLUME 3, Number: | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | VOLUME 4, Number: | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

| VOLUME 5, Number: | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||

| You can find our PDF EDITION CONTENTS AND COVERS on our PDF EDITION BACK ISSUES PAGE | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Home page | Subscribe (print edition) | Selected articles | Our publications | Our mailing lists |

| PDF edition | Subscribe (PDF edition) | Back issue contents | Autism books | Contact us |